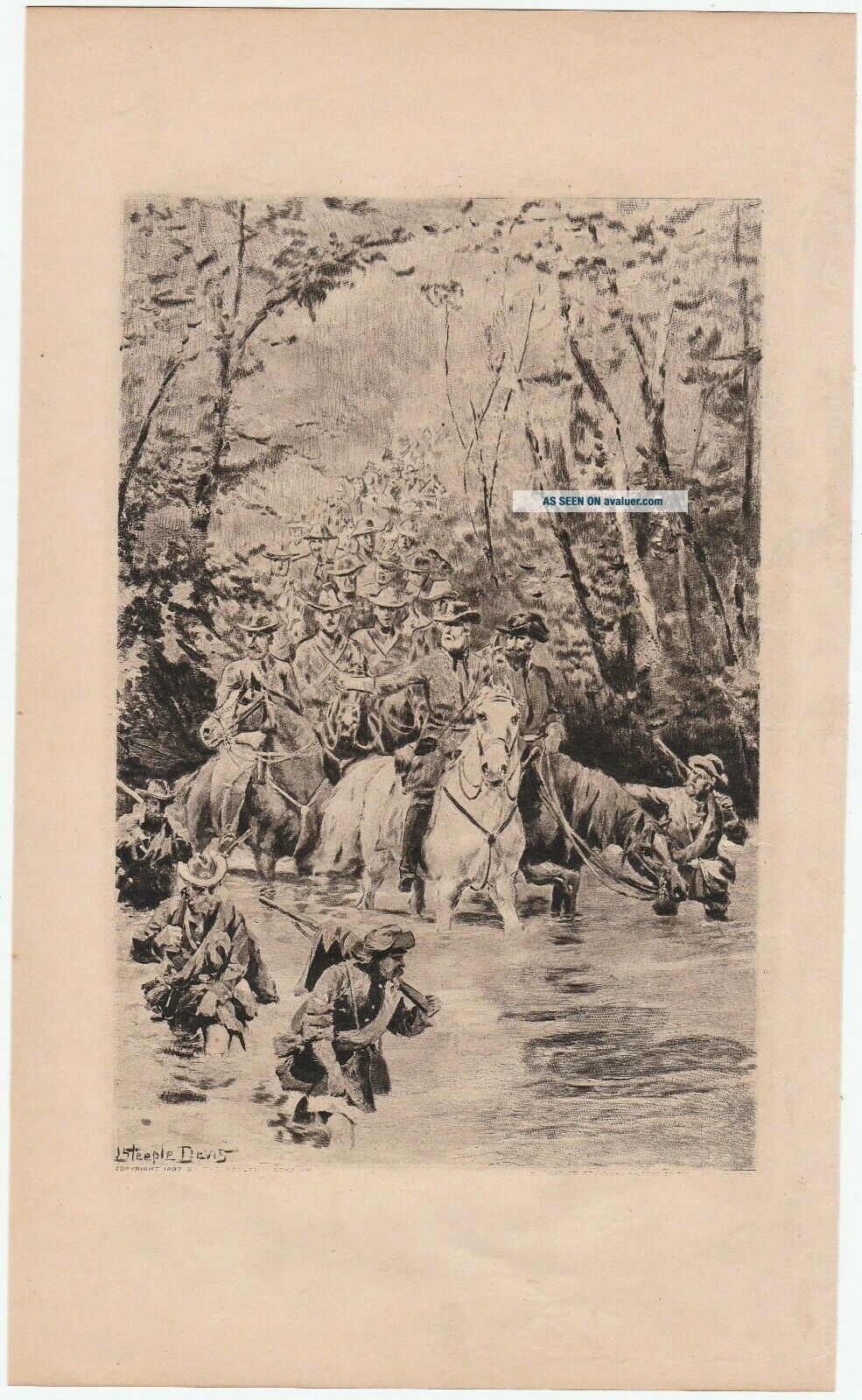

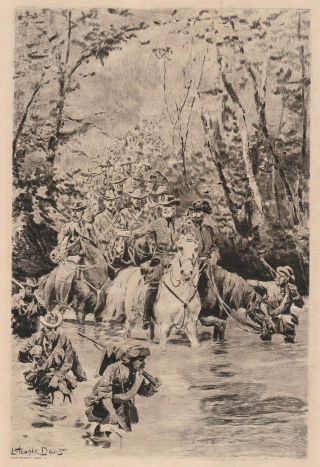

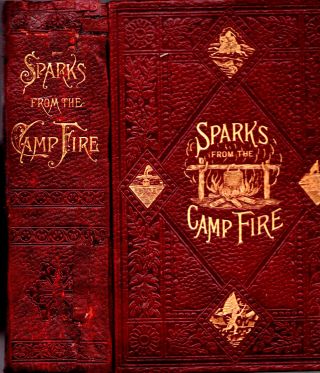

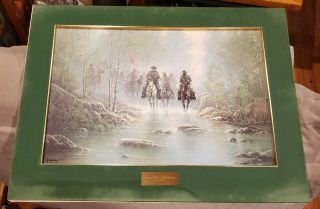

RARE Antique Print 1897 Civil War Gettysburg Robert E Lee Invades North By Davis

Item History & Price

| Reference Number: Avaluer:237846 | Modified Item: No |

| Country/Region of Manufacture: United States |

Antique - Old Original Print

Lee's Invasion of the North

[1863 - Gettysburg Campaign]

by

J. Steeple Davis

1897

For offer - a very nice old print! Fresh from an estate in Upstate NY. Never offered on the market until now. Vintage, Old, antique, Original - NOT a Reproduction - Guaranteed !! This print shows Lee on his horse with his army, invading the North - 1863 Gettysburg campaign. Dated at lower left corner, with... artists signature. Looks to be printed on Japan paper. Entire print measures 9 7/8 x 6. Small thin, tissue sheet with title and information also included, which is smaller. In good to very good condition. A few small areas of paper remains on left edge on back. Please see photos. If you collect American art history, Americana, Western culture, military, etc., this is a nice one for your paper or ephemera collection. Combine shipping on multiple bid wins! 02033

The Gettysburg Campaign was a military invasion of Pennsylvania by the main Confederate army under General Robert E. Lee in summer 1863. The Union won a decisive victory at Gettysburg July 1–3, with heavy casualties on both sides. Lee managed to escape back to Virginia with most of his army. It was a turning point in the American Civil War, with Lee increasingly pushed back toward Richmond until his surrender in April 1865. After his victory in the Battle of Chancellorsville, Lee's Army of Northern Virginia moved north for a massive raid designed to obtain desperately needed supplies, to undermine civilian morale in the North, and to encourage anti-war elements. The Union Army of the Potomac was commanded by Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker and then (from June 28) by Maj. Gen. George G. Meade.

Lee's army slipped away from Federal contact at Fredericksburg, Virginia, on June 3, 1863. The largest predominantly cavalry battle of the war was fought at Brandy Station on June 9. The Confederates crossed the Blue Ridge Mountains and moved north through the Shenandoah Valley, capturing the Union garrison at Winchester, Virginia, in the Second Battle of Winchester, June 13–15. Crossing the Potomac River, Lee's Second Corps advanced through Maryland and Pennsylvania, reaching the Susquehanna River and threatening the state capital of Harrisburg. However, the Army of the Potomac was in pursuit and had reached Frederick, Maryland, before Lee realized his opponent had crossed the Potomac. Lee moved swiftly to concentrate his army around the crossroads town of Gettysburg.

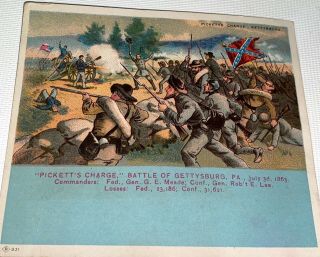

The Battle of Gettysburg was the largest of the war. Starting as a chance meeting engagement on July 1, the Confederates were initially successful in driving Union cavalry and two infantry corps from their defensive positions, through the town, and onto Cemetery Hill. On July 2, with most of both armies now present, Lee launched fierce assaults on both flanks of the Union defensive line, which were repulsed with heavy losses on both sides. On July 3, Lee focused his attention on the Union center. The defeat of his massive infantry assault, Pickett's Charge, caused Lee to order a retreat that began the evening of July 4.

The Confederate retreat to Virginia was plagued by bad weather, difficult roads, and numerous skirmishes with Union cavalry. However, Meade's army did not maneuver aggressively enough to prevent Lee from crossing the Potomac to safety on the night of July 13–14.

BackgroundLee's plansMain article: Battle of ChancellorsvilleFurther information: Eastern Theater of the American Civil War and American Civil War

Northern Virginia, Maryland and Pennsylvania (1861-1865)

Gettysburg Campaign, (1863)Shortly after Lee's Army of Northern Virginia defeated Hooker's Army of the Potomac during the Chancellorsville Campaign (April 30 – May 6, 1863), Lee decided upon a second invasion of the North. Such a move would upset Union plans for the summer campaigning season, give Lee the ability to maneuver his army away from its defensive positions behind the Rappahannock River, and allow the Confederates to live off the bounty of the rich northern farms while giving war-ravaged Virginia a much needed break. Lee's army could also threaten Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, and encourage the growing peace movement in the North.

Lee had numerous misunderstandings that shaped his strategy. Lee misread Northern opinion by his reliance on anti-war Copperhead newspapers for northern public opinion. Reading them, he assumed the Yankees must be just as war weary as southerners, and did not appreciate the determination of the Lincoln Administration. Lee did know he was seriously short of supplies for his own army, so he planned the campaign primarily as a full-scale raid that would seize supplies.[10] He wrote:

If we can baffle them [Yankees] in their various designs this year & our people are true to our cause...our success will be certain.... [and] next year there will be a great change in public opinion at the North. The Republicans will be destroyed [in the 1864 presidential election] & I think the friends of peace will become so strong as that the next administration will go in on that basis. We have only therefore to resist manfully.[11][12]Lee was overconfident of the morale and equipment of his "invincible" veterans; he fantasized about a definitive war-winning triumph:

[The Yankees will be] broken down with hunger and hard marching, strung out on a long line and much demoralized when they come into Pennsylvania. I shall throw an overwhelming force on their advance, crush it, follow up the success, drive one corps back on another, and by successive repulses and surprises, before they can concentrate, create a panic and virtually destroy the army. [Then] the war will be over and we shall achieve the recognition of our independence.[13]The Confederate government had a different strategy. It wanted Lee to reduce Union pressure threatening their garrison at Vicksburg, Mississippi, but he rejected its suggestions to send troops to provide direct aid, arguing for the value of a concentrated blow in the Northeast.[14]

In essence, Lee's strategy was identical to the one he employed in the Maryland Campaign of 1862. Furthermore, after Chancellorsville he had supreme confidence in the men of his army, assuming they could handle any challenge he gave them.[15]

Opposing forcesFurther information: Battle of Gettysburg § Opposing forcesConfederate forcesLee's movement started on the first of June and within a short time was well on its way through Maryland, with Union forces moving north along parallel lines. Lee's cavalry, under General Jeb Stuart had the primary mission of gathering intelligence on where the enemy position was, but Stuart failed and instead raided some supply trains. He did not rejoin Lee until the battle was underway. Stuart had taken all Lee's best cavalry, leaving the main army with two third-rate, ill-equipped, poorly led brigades that could not handle the reconnaissance challenge in hostile country.[16]

Lee's armies threatened Harrisburg, Washington, Baltimore and even Philadelphia. Local militia units hurriedly formed to oppose Lee, but they were inconsequential in the face of a large, battle-hardened attack force. Gettysburg was a crossroads junction in heavily wooded areas. Over three days, July 1–3, Confederate forces arrived piecemeal from the northwest, while Union forces arrived piecemeal from the east. By July 1 Meade was to the south of Lee—Lee's retreat was cut off and he had to fight, and had to win.[17]

Union forcesJoseph Hooker, commanding the Army of the Potomac, was, as Lee had calculated, indeed tardy and afraid to fight Lee. He wanted to attack Richmond, but Lincoln vetoed that idea as impossible of success and replaced Hooker with George Meade. The new commander brooked no delay in chasing the rebels north.[18]

Lee underestimated his new foe, expecting him to be easy to anticipate and slow to respond, much like Hooker. Lee was blinded for a week by the failure of Jeb Stuart's cavalry to provide timely reconnaissance. Stuart was, in fact, miles away sacking a mule-drawn supply train. Stuart had trouble finding Lee; he solved his intelligence problem by reading a Philadelphia newspaper that accurately reported Lee's location. The news was a day old, however, and Stuart, slowed down by booty, did not arrive at Gettysburg until July 2. The Confederates were often aided by uncensored newspaper reports of the movements of Union forces. Hooker tried to censor the newspapers, but reporters and editors evaded his restrictions and the South often had accurate reports of Union strength.[19]

Meanwhile, Meade was close behind Lee, and had cut off the line of retreat back to Virginia. Lee had to fight, but first he had to rush to reassemble his scattered forces at the crossroads town of Gettysburg before Meade defeated them piecemeal. Lee had 60, 000 infantry and 10, 200 cavalry (Meade's staff estimated Lee had 140, 000). This time it was Lee's turn to be fooled; he gullibly swallowed misinformation that suggested Meade had twice as many soldiers, when in fact he had 86, 000.[20]

Even though the main Confederate army was marching through Pennsylvania, Lincoln was unable to give Meade more firepower. The vast majority of the 700, 000 Federal soldiers (except for Grant's 70, 000 near Vicksburg) were noncombatants, held static defensive posts that Lincoln feared to uncover, or like Rosecrans at Nashville, they were afraid to move. Urgently the President called for 100, 000 civilian militiamen to turn out for the emergency; being unorganized, untrained, unequipped and poorly led, they were more trouble than they were worth. When the battle began they broke and ran away.[21]

Campaign timelineThe battles of the Gettysburg Campaign were fought in the following sequence; they are described in the context of logical, sometimes overlapping divisions of the campaign.

Action Dates Section of campaignBattle of Brandy Station June 9, 1863 Brandy StationSecond Battle of Winchester June 13–15 WinchesterBattle of Aldie June 17 Hooker's pursuitBattle of Middleburg June 17–19 Hooker's pursuitBattle of Upperville June 21 Hooker's pursuitBattle of Fairfax Court House June 27 Stuart's rideSkirmish of Sporting Hill June 30 Invasion of PennsylvaniaBattle of Hanover June 30 Stuart's rideBattle of Gettysburg July 1–3 GettysburgBattle of Carlisle July 1 Stuart's rideBattle of Hunterstown July 2 Stuart's rideBattle of Fairfield July 3 RetreatBattle of Monterey Pass July 4–5 RetreatBattle of Williamsport July 6–16 RetreatBattle of Boonsboro July 8 RetreatBattle of Funkstown July 10 RetreatBattle of Manassas Gap July 23 RetreatLee's advance to Gettysburg

Gettysburg Campaign (through July 3) Confederate UnionCavalry movements are shown with dashed lines.On June 3, 1863, Lee's army began to slip away northwesterly from Fredericksburg, Virginia, leaving A.P. Hill's Corps in fortifications above Fredericksburg to cover the departure of the army, protect Richmond from any Union incursion across the Rappahannock, and pursue the enemy if Hill thought it advantageous.[note 1] By the following morning, Hooker's chief of staff, General Daniel Butterfield, had received various reports that at least a portion of the Confederate Army was moving.[note 2] The next day, June 5, Hooker canceled all leave and army furloughs and instructed that all troops be prepared to march if necessary.[note 3] In the meantime, Longstreet's and Ewell's corps were camped in and around Culpeper.[25] With more Union reports intimating that Lee had moved a large portion of his army, Hooker ordered Sedgwick to conduct a reconnaissance in force across the Rappahannock River.

A small skirmish began shortly after 5:00 p.m. as Vermont and New Jersey troops, supported by a heavy Federal artillery bombardment, paddled across the river and overran Confederate positions on the southern bank.[26] As a precaution, Lee temporarily halted Ewell's Corps, but when he saw that Hooker would not press the Fredericksburg line to bring on a battle, he ordered Ewell to continue. The same day as Federal troops crossed the river, General Buford wrote that he had received credible information that "all of the available cavalry of the Confederacy" was in Culpeper County.[27] On June 7, George H. Sharpe, head of the Bureau of Military Information, erroneously reported to Hooker that, while J. E. B. Stuart was preparing a large cavalry raid, Lee's infantry would be withdrawing to Richmond.[28] Hooker decided to preemptively attack the Confederate cavalry force in Culpeper and ordered Cavalry Corps commander Alfred Pleasonton to command the assault.[note 4]

Lee rejoined the leading elements of his army in Culpeper on June 7 and ordered Albert G. Jenkins' cavalry to advance northward through the Shenandoah Valley.[note 5][31] He also wrote to John D. Imboden and ordered him to attract Union forces in Hampshire County and to disrupt their communications and logistics as well as acquire cattle for use by the Confederate Army.[note 6] To support these movements, Lee wrote to General Samuel Jones and asked him to spare any troops that he could.[note 7] The following day, he wrote to James Seddon, Confederate Secretary of War, and attempted to persuade him to send troops currently in North Carolina to reinforce either his army or Confederate forces in the west.[note 8] On June 9, Lee ordered Stuart to cross the Rappahannock and raid Union forward positions, screening the Confederate Army from observation or interference as it moved north. Anticipating this imminent offensive action, Stuart ordered his troopers into bivouac around Brandy Station.[35]

Brandy Station Further information: Battle of Brandy Station

Overview of the Battle of Brandy StationAlfred Pleasonton's combined arms force consisted of 8, 000 cavalrymen and 3, 000 infantry, [36] while Stuart commanded about 9, 500 Confederates.[37] Pleasonton's attack plan called for a double envelopment of the enemy. The wing under Brigadier General John Buford would cross the river at Beverly's Ford, two miles (3 km) northeast of Brandy Station. At the same time, David McMurtrie Gregg's wing would cross at Kelly's Ford, six miles (10 km) downstream to the southeast. However, Pleasonton was unaware of the precise disposition of the enemy and he incorrectly assumed that his force was substantially larger than the Confederates he faced.[38]

About 4:30 a.m. on June 9, Buford's column crossed the Rappahannock River and almost immediately encountered Confederate forces.[39] After overcoming their shock at Buford's surprise attack, Confederate forces rallied and managed to check the Union force near St. James Church.[40][39] Gregg's force, delayed in getting the leading force into position, finally attacked across Kelly's Ford at 9:00 a.m. Gregg's force divided once across the Rappahannock with one section attacking west toward Stevensburg and the second force pushing north to Brandy Station.[39] Between Gregg and the St. James action was a prominent ridge called Fleetwood Hill, which had been Stuart's headquarters the previous night. Stuart, surprised a second time by Gregg's forces threatening his rear, sent regiments from St. James to check the Union advance in the south. When Gregg's men charged up the western slope and neared the crest, the lead elements of Grumble Jones' brigade rode over the crown.[41]

For several hours there was desperate fighting on the slopes of the hill as many confusing charges and counter-charges swept back and forth.[39] The section of Union troops sent to Stevensburg were bluffed into withdrawing and turned eastward to reinforce Gregg on Fleetwood Hill. Generals Lee and Ewell rode out to Brandy Station to observe the battle and Lee ordered infantry reinforcements under Robert E. Rodes moved within a mile of the battle, still concealed, in case the Union broke through Stuart's lines.[42] Meanwhile, as Buford's forces at St. James began to make headway, Pleasonton ordered a withdrawal of all Union forces across the Rappahannock. As the threat to Confederate positions at Brandy Station lifted, Rodes withdrew his infantry back to their camp at Pony Mountain. By 9:00 p.m., all Union troops were across the river.[39]

Brandy Station was the largest predominantly cavalry fight of the war, and the largest to take place on American soil.[43] It was a tactical draw, although Pleasonton withdrew before finding the location of Lee's infantry nearby and Stuart claimed a victory, attempting to disguise the embarrassment of a cavalry force being surprised as it was by Pleasonton. The battle established the emerging reputation of the Union cavalry as a peer of the Confederate mounted arm.[44]

Winchester Further information: Second Battle of WinchesterAfter Brandy Station, a variety of Union sources reported the presence of Confederate infantry at Culpeper and Brandy Station.[note 9] Hooker did not immediately act on this information. The day after the battle, Ewell's Corps began marching toward the Shenandoah Valley.[46] Lee intended Ewell to clear the valley of Federal forces while Longstreet's Corps marched east of the Blue Ridge Mountains. A.P. Hill would then march his corps through the valley as well. On June 12, the leading elements of Lee's army were passing through the Chester Gap.[46]

At the same time, Hooker still believed that Lee's army was positioned on the west bank of the Rappahannock, between Fredricksburg and Culpeper and that it outnumbered his own.[note 10] Hooker had proposed to march on Richmond after the battle at Brandy Station, but Lincoln had replied that "Lee's army, not Richmond, is your true objective."[48] Meanwhile, Ewell's Corps was passing Front Royal and approaching Winchester.

The Union garrison was commanded by Major General Robert H. Milroy and consisted of 6, 900 troops posted in Winchester itself and a detachment of 1, 800 men ten miles (16 km) east in Berryville, Virginia.[49] The Union defenses consisted of three forts on high ground just outside the town. Milroy's tenure at Winchester had been marked by incivility toward the civilian population, who resented his oppressive rule, and the Confederate troops were eager to destroy his force. General-in-chief Henry Halleck did not want any Union force stationed in Winchester beyond what was necessary as an outpost to monitor Confederate movement and repeatedly ordered Milroy's superior, Maj. Gen. Robert C. Schenck of the Middle Department, to withdraw the surplus force to Harpers Ferry.[note 11] Schenck, however, did not comply and, unaware that Lee's infantry were approaching, did not issue any orders for Milroy to withdraw immediately from Winchester before June 13.[note 12] By then, Milroy's position was in extreme danger from a superior Confederate force.

Ewell planned to defeat the Union garrison by sending Allegheny Johnson and Jubal Early's divisions directly to Winchester while Rodes' division maneuvered east to defeat the Union detachment at Berryville and wheel north toward Martinsburg.[49][51] These movements effectively surrounded the Federal garrison by 23, 000 Confederate troops.[52] On the 13th, Milroy's telegraph connection with Harpers Ferry and Washington was cut by Ewell's troops. The Berryville detachment escaped Rodes' division and fell back on Winchester while Rodes' men continued north to Martinsburg. Though Ewell was initially hesitant about assaulting the defenses at Winchester, Early discovered that there was an unguarded hill west of the fortifications that dominated the battlefield.[51]

By 11 a.m. on June 14, Early began moving his forces covertly to take that position. To distract the Union, Ewell ordered demonstrations by John B. Gordon's brigade and the Maryland Line.[53] At 6 p.m., Confederate artillery opened fire on the Union's West Fort and the brigade of Brig. Gen. Harry T. Hays led the charge that captured the fort and a Union battery. As darkness fell, Milroy belatedly decided to retreat from his two remaining forts.[54]

Anticipating the movement, Ewell ordered Johnson to march northwest and block the Union escape route. At 3:30 a.m. on June 15, Johnson's column intercepted Milroy's on the Charles Town Road. Although Milroy ordered his men to fight their way out of the situation, when the Stonewall Brigade arrived just after dawn to cut the turnpike to the north, Milroy's men began to surrender in large numbers. Milroy escaped personally but the Second Battle of Winchester cost the Union about 4, 450 casualties (4, 000 captured) out of 7, 000 engaged, while the Confederates lost only 250 of 12, 500 engaged.[55]

Hooker's pursuit Further information: Battle of Aldie, Battle of Middleburg, and Battle of Upperville"Fighting Joe" Hooker did not know Lee's intentions, and Stuart's cavalry masked the Confederate army's movements behind the Blue Ridge effectively. He initially conceived the idea of reacting to Lee's absence by seizing unprotected Richmond, Virginia, the Confederate capital. But President Abraham Lincoln sternly reminded him that Lee's army was the true objective. His orders were to pursue and defeat Lee but to stay between Lee and Washington and Baltimore. On June 14, the Army of the Potomac departed Fredericksburg and reached Manassas Junction on June 16. Hooker dispatched Pleasonton's cavalry again to punch through the Confederate cavalry screen to find the main Confederate army, which led to three minor cavalry battles from June 17 through June 21 in the Loudoun Valley.[56]

Pleasonton ordered David McM. Gregg's division from Manassas Junction westward down the Little River Turnpike to Aldie. Aldie was tactically important in that near the village the Little River Turnpike intersected both of the turnpikes leading through Ashby's Gap and Snickers Gap into the Valley. The Confederate cavalry brigade of Col. Thomas T. Munford was entering Aldie from the west, preparing to bivouac, when three brigades of Gregg's division entered from the east at about 4 p.m. on June 17, surprising both sides. The resulting Battle of Aldie was a fierce mounted fight of four hours with about 250 total casualties. Munford withdrew toward Middleburg.[57]

While the fighting occurred at Aldie, the Union cavalry brigade of Col. Alfred N. Duffié arrived south of Middleburg in the late afternoon and drove in the Confederate pickets. Stuart was in the town at the time and managed to escape before his brigades under Munford and Beverly Robertson routed Duffié in an early morning assault on June 18. The primary action of the Battle of Middleburg occurred on the morning of June 19 when Col. J. Irvin Gregg's brigade advanced west from Aldie and attacked Stuart's line on a ridge west of Middleburg. Stuart repulsed Gregg's charge, counterattacked, then fell back to defensive positions one-half mile (800 m) to the west.[58]

On June 21, Pleasonton again attempted to break Stuart's screen by advancing on Upperville, nine miles (14 km) to the west of Middleburg. The cavalry brigades of Irvin Gregg and Judson Kilpatrick were accompanied by infantry from Col. Strong Vincent's brigade on the Ashby's Gap Turnpike. Buford's cavalry division moved northwest against Stuart's left flank, but made little progress against Grumble Jones's and John R. Chambliss's brigades. The Battle of Upperville ended as Stuart conducted a fierce fighting withdrawal and took up a strong defensive position in Ashby's Gap.[59]

After successfully defending his screen for almost a week, Stuart found himself motivated to begin the most controversial adventure of his career, Stuart's raid around the eastern flank of the Union Army.[60]

Hooker's significant pursuit with the bulk of his army began on June 25, after he learned that the Army of Northern Virginia had crossed the Potomac River. He ordered the Army of the Potomac to cross into Maryland and concentrate at Middletown (Slocum's XII Corps) and Frederick (the rest of the army, led by Reynolds's advance wing—the I, III, and XI Corps).[61]

The invasion of Pennsylvania Further information: Skirmish of Sporting HillPresident Lincoln issued a proclamation calling for 100, 000 volunteers from four states to serve a term of six months "to repel the threatened and imminent invasion of Pennsylvania."[62] Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin called for 50, 000 volunteers to take arms as volunteer militia; only 7, 000 initially responded, and Curtin asked for help from the New York State Militia. Gov. Joel Parker of New Jersey also responded by sending troops to Pennsylvania. The War Department created the Department of the Susquehanna, commanded by Maj. Gen. Darius N. Couch, to coordinate defensive efforts in Pennsylvania.[63]

Pittsburgh, Harrisburg, and Philadelphia were considered potential targets and defensive preparations were made. In Harrisburg, the state government removed its archives from the town for safekeeping. In much of southern Pennsylvania, the Gettysburg campaign became widely known as the "Emergency of 1863." The military campaign resulted in the displacement of thousands of refugees from Maryland and Pennsylvania who fled northward and eastward to avoid the oncoming Confederates, and resulted in a shift in demographics in several southern Pennsylvania boroughs and counties.[64]

Although a primary purpose of the campaign was for the Army of Northern Virginia to accumulate food and supplies outside of Virginia, Lee gave strict orders (General Order 72) to his army to minimize any negative impacts on the civilian population.[65] Food, horses, and other supplies were generally not seized outright, although quartermasters reimbursing Northern farmers and merchants using Confederate money were not well received. Various towns, most notably York, Pennsylvania, were required to pay indemnities in lieu of supplies, under threat of destruction. During the invasion, the Confederates seized some 40 northern African Americans, a few of whom were escaped fugitive slaves but most were freemen. They were sent south under guard into slavery.[66][67]

Ewell's corps continued to push deeper into Pennsylvania, with two divisions heading through the Cumberland Valley to threaten Harrisburg, while Jubal Early's division of Ewell's Corps marched eastward over the South Mountain range, occupying Gettysburg on June 26 after a brief series of skirmishes with state emergency militia and two companies of cavalry. Early laid the borough under tribute but did not collect any significant quantities of supplies. Soldiers burned several railroad cars and a covered bridge, and they destroyed nearby rails and telegraph lines. The following morning, Early departed for adjacent York County.[68]

The brigade of Brig. Gen. John B. Gordon of Early's division reached the Susquehanna on June 28, where militia guarded the 5, 629-foot-long (1, 716 m) covered bridge at Wrightsville. Gordon's artillery fire caused the well fortified militiamen to retreat and burn the bridge. Confederate cavalry under the command of Brig. Gen. Albert G. Jenkins raided nearby Mechanicsburg on June 28 and skirmished with militia at Sporting Hill on the west side of Camp Hill on June 29. The Confederates then pressed on to the outer defenses of Fort Couch, where they skirmished with the outer picket line for over an hour, the northernmost engagement of the Gettysburg Campaign. They later withdrew in the direction of Carlisle.[69]

Stuart's raid Further information: Battle of Hanover, Battle of Carlisle, and Battle of HunterstownJeb Stuart enjoyed the glory of circumnavigating an enemy army, which he had done on two previous occasions in 1862, during the Peninsula Campaign and at the end of the Maryland Campaign. It is possible that he had the same intention when he spoke to Robert E. Lee following the Battle of Upperville. He certainly needed to erase the stain on his reputation represented by his surprise and near defeat at the Battle of Brandy Station. The exact nature of Lee's order to Stuart on June 22 has been argued by the participants and historians ever since, but the essence was that he was instructed to guard the mountain passes with part of his force while the Army of Northern Virginia was still south of the Potomac and that he was to cross the river with the remainder of the army and screen the right flank of Ewell's Second Corps. Instead of taking a direct route north near the Blue Ridge Mountains, Stuart chose to reach Ewell's flank by taking his three best brigades (those of Wade Hampton, Fitzhugh Lee, and John R. Chambliss, the latter replacing the wounded W.H.F. "Rooney" Lee) between the Union army and Washington, moving north through Rockville to Westminster and on into Pennsylvania, hoping to capture supplies along the way and cause havoc near the enemy capital. Stuart and his three brigades departed Salem Depot at 1 a.m. on June 25.[70]

Unfortunately for Stuart's plan, the Union army's movement was underway and his proposed route was blocked by columns of Federal infantry from Hancock's II Corps, forcing him to veer farther to the east than either he or General Lee had anticipated. This prevented Stuart from linking up with Ewell as ordered and deprived Lee of the use of his prime cavalry force, the "eyes and ears" of the army, while advancing into unfamiliar enemy territory.[71]

Stuart's command reached Fairfax Court House, where they were delayed for half a day by the small but spirited Battle of Fairfax Court House (June 1863) on June 27, and crossed the Potomac River at Rowser's Ford at 3 a.m. on June 28. Upon entering Maryland, the cavalrymen attacked the C & O Canal, one of the major supply lines for the Army of the Potomac, capturing canal boats and cargo. They entered Rockville on June 28, also a key wagon supply road between the Union Army and Washington, tearing down miles of telegraph wire and capturing a wagon train of 140 brand new, fully loaded wagons and mule teams. This wagon train would prove to be a logistical hindrance to Stuart's advance, but he interpreted Lee's orders as placing importance on gathering supplies. The proximity of the Confederate raiders provoked some consternation in the national capital and Meade dispatched two cavalry brigades and an artillery battery to pursue the Confederates. Stuart supposedly told one of his prisoners from the wagon train that were it not for his fatigued horses "he would have marched down the 7th Street Road [and] took Abe & Cabinet prisoners."[72]

Stuart had planned to reach Hanover, Pennsylvania, by the morning of June 28, but rode into Westminster, Maryland, instead late on the afternoon of June 29. Here his men clashed briefly with and overwhelmed two companies of the 1st Delaware Cavalry under Maj. Napoleon B. Knight, chasing them a long distance on the Baltimore road, which Stuart claimed caused a "great panic" in the city of Baltimore.[73]

Meanwhile, Union cavalry commander Alfred Pleasonton ordered his divisions to spread out in their movement north with the army, looking for Confederates. Judson Kilpatrick's division was on the right flank of the advance and passed through Hanover on the morning of June 30. The head of Stuart's column encountered Kilpatrick's rear as it passed through town and scattered it. The Battle of Hanover ended after Kilpatrick's men regrouped and drove the Confederates out of town. Stuart's brigades had been better positioned to guard their captured wagon train than to take advantage of the encounter with Kilpatrick. To protect his wagons and prisoners, he delayed until nightfall and then detoured around Hanover by way of Jefferson to the east, increasing his march by five miles (8 km). After a 20-mile (32 km) trek in the dark, his exhausted men reached Dover on the morning of July 1, the same time that his Confederate infantry colleagues began to fight Union cavalrymen under John Buford at Gettysburg.[74]

Leaving Hampton's Brigade and the wagon train at Dillsburg, Stuart headed for Carlisle, hoping to find Ewell. Instead, he found nearly 3, 000 Pennsylvania and New York militia occupying the borough. After lobbing a few shells into town during the early evening of July 1 and burning the Carlisle Barracks, Stuart concluded the so-called Battle of Carlisle and withdrew after midnight to the south towards Gettysburg. The fighting at Hanover, the long march through York County with the captured wagons, and the brief encounter at Carlisle slowed Stuart considerably in his attempt to rejoin the main army.[75]

Stuart and the bulk of his command reached Lee at Gettysburg the afternoon of July 2. He ordered Wade Hampton to take a position to cover the left rear of the Confederate battle lines. Hampton moved into position astride the Hunterstown Road four miles (6 km) northeast of town, blocking access for any Union forces that might try to swing around behind Lee's lines. Two brigades of Union cavalry from Judson Kilpatrick's division under Brig. Gens. George Armstrong Custer and Elon J. Farnsworth were probing for the end of the Confederate left flank. Custer attacked Hampton in the Battle of Hunterstown on the road between Hunterstown and Gettysburg, and Hampton counterattacked. When Farnsworth arrived with his brigade, Hampton did not press his attack, and an artillery duel ensued until dark. Hampton then withdrew towards Gettysburg to rejoin Stuart.[76]

Dix's advance against RichmondAs Lee's offensive strategy became clear, Union general-in-chief Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck planned a countermove that could take advantage of the now lightly defended Confederate capital of Richmond. He ordered the Union Department of Virginia, two corps under Maj. Gen. John A. Dix, to move on Richmond from its locations on the Virginia Peninsula (around Yorktown and Williamsburg) and near Suffolk. However, Halleck made the mistake of not explicitly ordering Dix to attack Richmond. The orders were to "threaten Richmond, by seizing and destroying their railroad bridges over the South and North Anna Rivers, and do them all the damage possible." Dix, a well-respected politician, was not an aggressive general, but he eventually contemplated attacking Richmond despite the vagueness of Halleck's instructions.[77]

On June 27, his men conducted a successful cavalry raid on Hanover Junction, led by Col. Samuel P. Spear, which defeated the Confederate regiment guarding the railroad junction, destroyed the bridge over the South Anna River and the quartermaster's depot, capturing supplies, wagons, and 100 prisoners including General Lee's son, Brig. Gen. W. H. F. "Rooney" Lee. On June 29, at a council of war, Dix and his lieutenants expressed concerns about their limited strength (about 32, 000 men) and decided to limit themselves to threatening gestures. Confederate Maj. Gen. D. H. Hill wrote that the Union advance on Richmond was "not a feint but a faint." The net effect of the operation was primarily psychological, causing the Confederates to hold back some troops from Lee's offensive to guard the capital.[78]

Meade assumes commandOn the evening of June 27, Lincoln sent orders relieving Hooker. Hooker had argued with Halleck about defending the garrison at Harpers Ferry and petulantly offered to resign, which Halleck and Lincoln promptly accepted. George Meade, a Pennsylvanian who was commanding the V Corps, was ordered to assume command of the Army of the Potomac early on the morning of June 28 in Frederick, Maryland. Meade was surprised by the change of command order, having previously expressed his lack of interest in the army command. In fact, when an officer from Washington woke him with the order, he assumed he was being arrested for some transgression. Despite having little knowledge of what Hooker's plans had been or the exact locations of the three columns moving quickly to the northwest, Meade kept up the pace. He telegraphed to Halleck, in accepting his new command, that he would "Move toward the Susquehanna, keeping Washington and Baltimore well covered, and if the enemy is checked in his attempt to cross the Susquehanna or if he turns toward Baltimore, to give him battle."[79]

Map showing the position of Big Pipe Creek in relation to GettysburgOn June 30, Meade's headquarters advanced to Taneytown, Maryland, and he issued two important orders. The first directed that a general advance in the direction of Gettysburg begin on July 1, a destination that was from 5 to 25 miles (8 to 40 km) away from each of his seven infantry corps. The second order, known as the Pipe Creek Circular, established a prospective line on Big Pipe Creek, which had been surveyed by his engineers as a strong defensive position. Meade had the option of occupying this position and hoping that Lee would attack him there; alternatively, it would represent a fall back position if the army got into trouble at Gettysburg.[80]

Lee concentrates his armyThe lack of Stuart's cavalry intelligence kept Lee unaware that his army's normally sluggish foe had moved as far north as it had. It was only after a spy hired by Longstreet, Henry Thomas Harrison, reported it that Lee found out his opponent had crossed the Potomac and was following him nearby. By June 29, Lee's army was strung out in an arc from Chambersburg (28 miles (45 km) northwest of Gettysburg) to Carlisle (30 miles (48 km) north of Gettysburg) to near Harrisburg and Wrightsville on the Susquehanna River. Ewell's Corps had almost reached the Susquehanna River and was prepared to menace Harrisburg, the Pennsylvania state capital. Early's Division occupied York, which was the largest Northern town to fall to the Confederates during the war. Longstreet and Hill were near Chambersburg.[81]

Lee ordered a concentration of his forces around Cashtown, located at the eastern base of South Mountain and 8 miles (13 km) west of Gettysburg.[82] On June 30, while part of Hill's Corps was in Cashtown, one of Hill's brigades, North Carolinians under Brig. Gen. J. Johnston Pettigrew, ventured toward Gettysburg. The memoirs of Maj. Gen. Henry Heth, Pettigrew's division commander, claimed that he sent Pettigrew to search for supplies in town—especially shoes.[83]

When Pettigrew's troops approached Gettysburg on June 30, they noticed Union cavalry under Brig. Gen. John Buford arriving south of town, and Pettigrew returned to Cashtown without engaging them. When Pettigrew told Hill and Heth about what he had seen, neither general believed that there was a substantial Federal force in or near the town, suspecting that it had been only Pennsylvania militia. Despite Lee's order to avoid a general engagement until his entire army was concentrated, Hill decided to mount a significant reconnaissance in force the following morning to determine the size and strength of the enemy force in his front. Around 5 a.m. on Wednesday, July 1, two brigades of Heth's division advanced to Gettysburg.[84]

Battle of Gettysburg Further information: Battle of Gettysburg, First Day, Second Day, Little Round Top, Cemetery Hill, Culp's Hill, Pickett's Charge, Third Day cavalry battles

Battlefield of Gettysburg (1863)

Battle of Gettysburg, July 1, 1863

Battle of Gettysburg, July 2

Battle of Gettysburg, July 3The two armies began to collide at Gettysburg on July 1, 1863. The first day proceeded in three phases as combatants continued to arrive at the battlefield. In the morning, two brigades of Confederate Maj. Gen. Henry Heth's division (of Hill's Third Corps) were delayed by dismounted Union cavalrymen under Brig. Gen. John Buford. As infantry reinforcements arrived under Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds from the I Corps, the Confederate assaults down the Chambersburg Pike were repulsed, although Gen. Reynolds was killed.[85]

By early afternoon, the Union XI Corps had arrived, and the Union position was in a semicircle from west to north of the town. Ewell's Second Corps began a massive assault from the north, with Maj. Gen. Robert E. Rodes's division attacking from Oak Hill and Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early's division attacking across the open fields north of town. The Union lines generally held under extremely heavy pressure, although the salient at Barlow's Knoll was overrun. The third phase of the battle came as Rodes renewed his assault from the north and Heth returned with his entire division from the west, accompanied by the division of Maj. Gen. W. Dorsey Pender.[86]

Heavy fighting in Herbst's Woods (near the Lutheran Theological Seminary) and on Oak Ridge finally caused the Union line to collapse. Some of the Federals conducted a fighting withdrawal through the town, suffering heavy casualties and losing many prisoners; others simply retreated. They took up good defensive positions on Cemetery Hill and waited for additional attacks. Despite discretionary orders from Robert E. Lee to take the heights "if practicable, " Richard Ewell chose not to attack. Historians have debated ever since how the battle might have ended differently if he had found it practicable to do so.[87]

On the second day, Lee attempted to capitalize on his first day's success by launching multiple attacks against the Union flanks. After a lengthy delay to assemble his forces and avoid detection in his approach march, Longstreet attacked with his First Corps against the Union left flank. His division under Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood attacked Little Round Top and Devil's Den. To Hood's left, Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws attacked the Wheatfield and the Peach Orchard. Although neither prevailed, the Union III Corps was effectively destroyed as a combat organization as it attempted to defend a salient over too wide a front. Gen. Meade rushed as many as 20, 000 reinforcements from elsewhere in his line to resist these fierce assaults. The attacks in this sector concluded with an unsuccessful assault by the Third Corps division of Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson against the Union center on Cemetery Ridge. That evening, Ewell's Second Corps turned demonstrations against the Union right flank into full-scale assaults on Culp's Hill and East Cemetery Hill, but both were repulsed. The Union army had occupied strong defensive positions, and Meade handled his forces well, resulting in heavy losses for both sides but leaving the disposition of forces on both sides essentially unchanged.[88]

After attacks on both Union flanks had failed the day and night before, Lee was determined to strike the Union center on the third day. He decided to support this attack with a renewed thrust on the Union right that was supposed to start in concert with his assault on the center. However, the fighting on Culp's Hill resumed early in the morning with a Union counterattack, hours before Longstreet could begin his attack on the center. The Union troops on fortified Culp's Hill had been reinforced and the Confederates made no progress after multiple, futile assaults that lasted until noon. The infantry assault on Cemetery Ridge known as Pickett's Charge was preceded by a massive artillery bombardment at 1 p.m. that was meant to soften up the Union defense and silence its artillery, but it was largely ineffective. Approximately 12, 500 men in nine infantry brigades advanced over open fields for three-quarters of a mile (1, 200 m) under heavy Union artillery and rifle fire. Although some Confederates were able to breach the low stone wall that shielded many of the Union defenders, they could not maintain their hold and were repulsed with over 50% casualties.[89]

During and after Pickett's Charge on the third day, two significant cavalry battles also occurred: one approximately three miles (5 km) to the east, in the area known today as East Cavalry Field, the other southwest of the [Big] Round Top mountain (sometimes called South Cavalry Field). The East Cavalry Field fighting was an attempt by Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart's Confederate cavalry to get into the Federal rear and exploit any success that Pickett's Charge may have generated. Union cavalry under Brig. Gens. David McM. Gregg and George Armstrong Custer repulsed the Confederate advances. In South Cavalry Field, after Pickett's Charge had been defeated, reckless cavalry charges against the right flank of the Confederate Army, ordered by Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick, were easily repulsed.[90]

The three-day battle in and around Gettysburg resulted in the largest number of casualties in the American Civil War—between 46, 000 and 51, 000.[91] In conjunction with the Union victory at Vicksburg on July 4, Gettysburg is frequently cited as the war's turning point.[92]

Lee's retreat to Virginia Further information: Retreat from GettysburgLee managed to escape back to Virginia after a harrowing forced march in the face of flooded rivers. Meade took the blame for the failure to capture Lee's highly vulnerable and outnumbered army.[93]

Following Pickett's Charge, the Confederates returned to their positions on Seminary Ridge and prepared fortifications to receive a counterattack. When the Union attack had not occurred by the evening of July 4, Lee realized that he could accomplish nothing more in his campaign and that he had to return his battered army to Virginia. Lee started his Army of Northern Virginia in motion late the evening of July 4 towards Fairfield and Chambersburg. Cavalry under Brig. Gen. John D. Imboden was entrusted to escort the miles-long wagon train of supplies and wounded men that Lee wanted to take back to Virginia with him, using the route through Cashtown and Hagerstown to Williamsport, Maryland. Thousands of more seriously wounded soldiers were left behind in the Gettysburg area, along with medical personnel. However, despite casualties of over 20, 000 men, including a number of senior officers, the morale of Lee's army remained high and their respect for the commanding general was not diminished by their reverses.[94]

Unfortunately for the Confederate Army, however, once they reached the Potomac they would find it difficult to cross. Torrential rains that started on July 4 flooded the river at Williamsport, making fording impossible. Four miles (6 km) downstream at Falling Waters, Union cavalry destroyed Lee's lightly guarded pontoon bridge on July 4. The only way to cross the river was a small ferry at Williamsport. The Confederates could potentially be trapped, forced to defend themselves against Meade with their backs to the river.[95]

Gettysburg Campaign (July 5–14)The route of the bulk of Lee's army was through Fairfield and over Monterey Pass to Hagerstown. A small but important action that occurred while Pickett's Charge was still underway, the Battle of Fairfield, prevented the Union from blocking this route. Brig. Gen. Wesley Merritt's brigade departed from Emmitsburg with orders to strike the Confederate left and rear along Seminary Ridge. Merritt dispatched about 400 men from the 6th U.S. Cavalry to seize foraging wagons that had been reported in the area. Before they were able to reach the wagons, the 7th Virginia Cavalry, leading a column under Confederate Brig. Gen. William E. "Grumble" Jones, intercepted the regulars, but the U.S. cavalrymen repulsed the Virginians. Jones sent in the 6th Virginia Cavalry, which successfully charged and swarmed over the Union troopers. There were 242 Union casualties, primarily prisoners, and 44 casualties among the Confederates.[96]

Imboden's journey was one of extreme misery, conducted during the torrential rains that began on July 4, in which the 8, 000 wounded men were forced to endure the weather and the rough roads in wagons without suspensions. The train was harassed throughout its march. At dawn on July 5, civilians in Greencastle ambushed the train with axes, attacking the wheels of the wagons, until they were driven off. That afternoon at Cunningham's Cross Roads, Union cavalry attacked the column, capturing 134 wagons, 600 horses and mules, and 645 prisoners, about half of whom were wounded. These losses so angered Stuart that he demanded a court of inquiry to investigate.[97]

Early on July 4 Meade sent his cavalry to strike the enemy's rear and lines of communication so as to "harass and annoy him as much as possible in his retreat." Eight of nine cavalry brigades (except Col. John B. McIntosh's of Brig. Gen. David McM. Gregg's division) took to the field. Col. J. Irvin Gregg's brigade (of his cousin David Gregg's division) moved toward Cashtown via Hunterstown and the Mummasburg Road, but all of the others moved south of Gettysburg. Brig. Gen. John Buford's division went directly from Westminster to Frederick, where they were joined by Merritt's division on the night of July 5.[98]

Late on July 4, Meade held a council of war in which his corps commanders agreed that the army should remain at Gettysburg until Lee acted, and that the cavalry should pursue Lee in any retreat. Meade decided to have Brig. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren take a division from Sedgwick's VI Corps to probe the Confederate line and determine Lee's intentions. By the morning of July 5, Meade learned of Lee's departure, but he hesitated to order a general pursuit until he had received the results of Warren's reconnaissance.[99]

The Battle of Monterey Pass began as Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick's cavalry division easily brushed aside Brig. Gen. Beverly Robertson's pickets and encountered a detachment of 20 men from the Confederate 1st Maryland Cavalry Battalion, under Capt. G. M. Emack, that was guarding the road to Monterey Pass. Aided by a detachment of the 4th North Carolina Cavalry and a single cannon, the Marylanders delayed the advance of 4, 500 Union cavalrymen until well after midnight. Kilpatrick ordered Brig. Gen. George A. Custer to charge the Confederates with the 6th Michigan Cavalry, which broke the deadlock and allowed Kilpatrick's men to reach and attack the wagon train. They captured or destroyed numerous wagons and captured 1, 360 prisoners—primarily wounded men in ambulances—and a large number of horses and mules.[100]

As Meade's infantry began to march in earnest in pursuit of Lee on the morning of July 7, Buford's division departed from Frederick to destroy Imboden's train before it could cross the Potomac. At 5 p.m. on July 7 his men reached within one-half mile (800 m) of the parked trains, but Imboden's command repulsed their advance. Buford heard Kilpatrick's artillery in the vicinity and requested support on his right. Kilpatrick's men had moved toward Hagerstown and pushed out the two small brigades of Chambliss and Robertson. However, infantry commanded by Brig. Gen. Alfred Iverson drove Kilpatrick's men through the streets of town. Stuart's remaining brigades came up and were reinforced by two brigades of Hood's Division and Hagerstown was recaptured by the Confederates. Kilpatrick chose to respond to Buford's request for assistance and join the attack on Imboden at Williamsport. Stuart's men pressured Kilpatrick's rear and right flank from their position at Hagerstown and Kilpatrick's men gave way and exposed Buford's rear to the attack. Buford gave up his effort when darkness fell.[101]

Lee's rear guard cavalry clashed with Federal cavalry in the South Mountain passes in the Battle of Boonsboro on July 8, delaying Union pursuit. In the Battle of Funkstown on July 10, Stuart's cavalry continued its efforts to delay Federal pursuit in an encounter near Funkstown, Maryland, which resulted in nearly 500 casualties on both sides. The fight also marked the first time since the Battle of Gettysburg that Union infantry engaged Confederate infantry in the same engagement. Stuart was successful in delaying Pleasonton's cavalry for another day.[102]

By July 9 most of the Army of the Potomac was concentrated in a five-mile (8 km) line from Rohrersville to Boonsboro. Other Union forces were in position to protect the outer flanks at Maryland Heights and at Waynesboro.[103] By July 11 the Confederates occupied a six-mile (10 km), highly fortified line on high ground with their right resting on the Potomac River near Downsville and the left about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) southwest of Hagerstown, covering the only road from there to Williamsport.[104]

Meade telegraphed to general-in-chief Henry W. Halleck on July 12 that he intended to attack the next day, "unless something intervenes to prevent it." He once again called a council of war with his subordinates on the night of July 12, which resulted in a postponement of an attack until reconnaissance of the Confederate position could be performed, which Meade conducted the next morning. By that time, Lee became frustrated waiting for Meade to attack him and was dismayed to see that the Federal troops were digging entrenchments of their own in front of his works. Confederate engineers had completed a new pontoon bridge over the Potomac, which had also subsided enough to be forded. Lee ordered a retreat to start after dark, with Longstreet's and Hill's corps and the artillery to use the pontoon bridge at Falling Waters and Ewell's corps to ford the river at Williamsport.[105]

On the morning of July 14, advancing Union skirmishers found that the entrenchments were empty. Cavalry under Buford and Kilpatrick attacked the rearguard of Lee's army, Maj. Gen. Henry Heth's division, which was still on a ridge about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from Falling Waters. The initial attack caught the Confederates by surprise after a long night with little sleep, and hand-to-hand fighting ensued. Kilpatrick attacked again and Buford struck them in their right and rear. Heth's and Pender's divisions lost numerous prisoners. Brig. Gen. J. Johnston Pettigrew, who had survived Pickett's Charge with a minor hand wound, was mortally wounded at Falling Waters. This minor success against Heth did not make up for the extreme frustration in the Lincoln administration about allowing Lee to escape. The president was quoted as saying, "We had them within our grasp. We had only to stretch forth our hands and they were ours. And nothing I could say or do could make the Army move."[106]

The two armies did not take up positions across from each other on the Rappahannock River for almost two weeks. On July 16 the cavalry brigades of Fitzhugh Lee and Chambliss held the fords on the Potomac at Shepherdstown to prevent crossing by the Federal infantry. The cavalry division under David Gregg approached the fords and the Confederates attacked them, but the Union cavalrymen held their position until dark before withdrawing.[107]

The Army of the Potomac crossed the Potomac River at Harpers Ferry and Berlin (now named Brunswick) on July 17–18. They advanced along the east side of the Blue Ridge Mountains, trying to interpose themselves between Lee's army and Richmond. On July 23, in the Battle of Manassas Gap, Meade ordered French's III Corps to cut off the retreating Confederate columns at Front Royal, by forcing passage through Manassas Gap. At first light, French began slowly pushing the Stonewall Brigade back into the gap. About 4:30 p.m., a strong Union attack drove the Confederates until they were reinforced by Maj. Gen. Robert E. Rodes's division and artillery. By dusk, the poorly coordinated Union attacks were abandoned. During the night, Confederate forces withdrew into the Luray Valley. On July 24, the Union army occupied Front Royal, but Lee's army was safely beyond pursuit.[108]

AftermathThe Gettysburg Campaign represented the final major offensive by Robert E. Lee in the Civil War. Afterward, all combat operations of the Army of Northern Virginia were in reaction to Union initiatives. Lee suffered over 27, 000 casualties during the campaign, [9] a price very difficult for the Confederacy to pay. The campaign met only some of its major objectives: it had disrupted Union plans for a summer campaign in Virginia, temporarily protecting the citizens and economy of that state, and it had allowed Lee's men to live off the bountiful Maryland and Pennsylvania countryside and plunder vast amounts of food and supplies that they carried back with them and that would allow them to continue the war. However, the myth of Lee's invincibility had been shattered and not a single Union soldier was removed from the Vicksburg Campaign to react to Lee's invasion of the North.[109] (Vicksburg surrendered on July 4, the day Lee ordered his retreat.) Union campaign casualties were approximately 30, 100.[110]

Meade was severely criticized for allowing Lee to escape, just as Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan had been after the Battle of Antietam. Under pressure from Lincoln, he launched two campaigns in the fall of 1863—Bristoe and Mine Run—that attempted to defeat Lee. Both were failures. He also suffered humiliation at the hands of his political enemies in front of the Joint Congressional Committee on the Conduct of the War, questioning his actions at Gettysburg and his failure to defeat Lee during the retreat to the Potomac.[111]

On November 19, 1863, Abraham Lincoln spoke at the dedication ceremonies for the national cemetery created at the Gettysburg battlefield. His Gettysburg Address redefined the war, calling for a "new birth of freedom" in the nation, which established the destruction of slavery as an implied goal.[112]

See also Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gettysburg campaign.Troop engagements of the American Civil War, 1863List of costliest American Civil War land battlesList of Medal of Honor recipients for the Gettysburg CampaignGettysburg Cyclorama, a painting by the French artist Paul Philippoteaux depicting Pickett's ChargeGettysburg Address

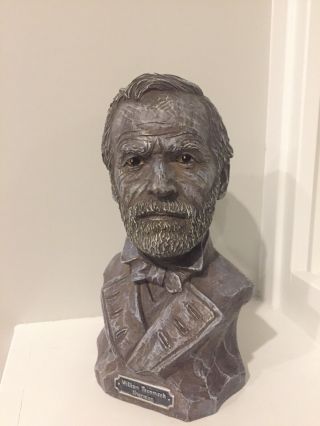

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was an American and Confederate soldier, best known as a commander of the Confederate States Army. He commanded the Army of Northern Virginia in the American Civil War from 1862 until his surrender in 1865. A son of Revolutionary War officer Henry "Light Horse Harry" Lee III, Lee was a top graduate of the United States Military Academy and an exceptional officer and military engineer in the United States Army for 32 years. During this time, he served throughout the United States, distinguished himself during the Mexican–American War, and served as Superintendent of the United States Military Academy.

When Virginia declared its secession from the Union in April 1861, Lee chose to follow his home state, despite his desire for the country to remain intact and an offer of a senior Union command.[1] During the first year of the Civil War, Lee served as a senior military adviser to Confederate President Jefferson Davis. Once he took command of the main field army in 1862 he soon emerged as a shrewd tactician and battlefield commander, winning most of his battles, all against far superior Union armies.[2][3] Lee's strategic foresight was more questionable, and both of his major offensives into Union territory ended in defeat.[4][5][6] Lee's aggressive tactics, which resulted in high casualties at a time when the Confederacy had a shortage of manpower, have come under criticism in recent years.[7] Lee surrendered his entire army to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. By this time, Lee had assumed supreme command of the remaining Southern armies; other Confederate forces swiftly capitulated after his surrender. Lee rejected the proposal of a sustained insurgency against the Union and called for reconciliation between the two sides.

In 1865, after the war, Lee was paroled and signed an oath of allegiance, asking to have his citizenship of the United States restored. Lee's application was misplaced; as a result, he did not receive a pardon and his citizenship was not restored.[8] In 1865, Lee became president of Washington College (later Washington and Lee University) in Lexington, Virginia; in that position, he supported reconciliation between North and South.[9] Lee accepted "the extinction of slavery" provided for by the Thirteenth Amendment, but publicly opposed racial equality and granting African Americans the right to vote and other political rights.[10][11][12] Lee died in 1870. In 1975, the U.S. Congress posthumously restored Lee's citizenship effective June 13, 1865.[8]

Lee opposed the construction of public memorials to Confederate rebellion on the grounds that they would prevent the healing of wounds inflicted during the war.[9] Nevertheless, after his death, Lee became an icon used by promoters of "Lost Cause" mythology, who sought to romanticize the Confederate cause and strengthen white supremacy in the South.[9] Later in the 20th century, particularly following the civil rights movement, historians reassessed Lee; his reputation fell based on his failure to support rights for freedmen after the war, and even his strategic choices as a military leader fell under scrutiny.[11][13]

Early life and career

Stratford Hall, Westmoreland Countythe family seat, Lee's birthplace

Oronoco Street, Alexandria, Virginia"Lee Corner" propertiesLee, a white Southerner, was born at Stratford Hall Plantation in Westmoreland County, Virginia, to Major General Henry Lee III (Light Horse Harry) (1756–1818), Governor of Virginia, and his second wife, Anne Hill Carter (1773–1829). His birth date has traditionally been recorded as January 19, 1807, but according to the historian Elizabeth Brown Pryor, "Lee's writings indicate he may have been born the previous year."[14]

One of Lee's great grandparents, Henry Lee I, was a prominent Virginian colonist of English descent.[15] Lee's family is one of Virginia's first families, descended from Richard Lee I, Esq., "the Immigrant" (1618–1664), from the county of Shropshire in England.[16]

Lee's mother grew up at Shirley Plantation, one of the most elegant homes in Virginia.[17] Lee's father, a tobacco planter, suffered severe financial reverses from failed investments.[18]

Little is known of Lee as a child; he rarely spoke of his boyhood as an adult.[19] Nothing is known of his relationship with his father who, after leaving his family, mentioned Robert only once in a letter. When given the opportunity to visit his father's Georgia grave, he remained there only briefly; yet, during his time as president of Washington College, he defended his father in a biographical sketch while editing Light Horse Harry's memoirs.[20]

Coat of Arms of Robert E. LeeIn 1809, Harry Lee was put in debtors prison; soon after his release the following year, Harry and Anne Lee and their five children moved to a small house on Cameron Street in Alexandria, Virginia, both because there were then high quality local schools there, and because several members of her extended family lived nearby.[21] In 1811, the family, including the newly born sixth child, Mildred, moved to a house on Oronoco Street, still close to the center of town and with the houses of a number of Lee relatives close by.[22]

In 1812, Harry Lee was badly injured in a political riot in Baltimore and traveled to the West Indies. He would never return, dying when his son Robert was eleven years old.[23] Left to raise six children alone in straitened circumstances, Anne Lee and her family often paid extended visits to relatives and family friends.[24] Robert Lee attended school at Eastern View, a school for young gentlemen, in Fauquier County, and then at the Alexandria Academy, free for local boys, where he showed an aptitude for mathematics. Although brought up to be a practicing Christian, he was not confirmed in the Episcopal Church until age 46.[25]

Anne Lee's family was often supported by a relative, William Henry Fitzhugh, who owned the Oronoco Street house and allowed the Lees to stay at his home in Fairfax County, Ravensworth. When Robert was 17 in 1824, Fitzhugh wrote to the Secretary of War, John C. Calhoun, urging that Robert be given an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point. Fitzhugh wrote little of Robert's academic prowess, dwelling much on the prominence of his family, and erroneously stated the boy was 18. Instead of mailing the letter, Fitzhugh had young Robert deliver it.[26] In March 1824, Robert Lee received his appointment to West Point, but due to the large number of cadets admitted, Lee would have to wait a year to begin his studies there.[27][citation not found]

Lee entered West Point in the summer of 1825. At the time, the focus of the curriculum was engineering; the head of the Army Corps of Engineers supervised the school and the superintendent was an engineering officer. Cadets were not permitted leave until they had finished two years of study, and were rarely allowed off the Academy grounds. Lee graduated second in his class, behind only Charles Mason[28] (who resigned from the Army a year after graduation). Lee did not incur any demerits during his four-year course of study, a distinction shared by five of his 45 classmates. In June 1829, Lee was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers.[29] After graduation, while awaiting assignment, he returned to Virginia to find his mother on her deathbed; she died at Ravensworth on July 26, 1829.[30]

Ancestors of Robert E. LeeMilitary engineer career

Lee at age 31 in 1838, as a Lieutenant of Engineers in the U.S. ArmyOn August 11, 1829, Brigadier General Charles Gratiot ordered Lee to Cockspur Island, Georgia. The plan was to build a fort on the marshy island which would command the outlet of the Savannah River. Lee was involved in the early stages of construction as the island was being drained and built up.[31] In 1831, it became apparent that the existing plan to build what became known as Fort Pulaski would have to be revamped, and Lee was transferred to Fort Monroe at the tip of the Virginia Peninsula (today in Hampton, Virginia).[32][citation not found]

While home in the summer of 1829, Lee had apparently courted Mary Custis whom he had known as a child. Lee obtained permission to write to her before leaving for Georgia, though Mary Custis warned Lee to be "discreet" in his writing, as her mother read her letters, especially from men.[33] Custis refused Lee the first time he asked to marry her; her father did not believe the son of the disgraced Light Horse Harry Lee was a suitable man for his daughter.[34] She accepted him with her father's consent in September 1830, while he was on summer leave, [35] and the two were wed on June 30, 1831.[36]

Lee's duties at Fort Monroe were varied, typical for a junior officer, and ranged from budgeting to designing buildings.[37][citation not found] Although Mary Lee accompanied her husband to Hampton Roads, she spent about a third of her time at Arlington, though the couple's first son, Custis Lee was born at Fort Monroe. Although the two were by all accounts devoted to each other, they were different in character: Robert Lee was tidy and punctual, qualities his wife lacked. Mary Lee also had trouble transitioning from being a rich man's daughter to having to manage a household with only one or two slaves.[38] Beginning in 1832, Robert Lee had a close but platonic relationship with Harriett Talcott, wife of his fellow officer Andrew Talcott.[39]

Fort Monroe, HamptonLee's early duty station

Fort Des Moines, MontroseLee's hand-drawn sketchLife at Fort Monroe was marked by conflicts between artillery and engineering officers. Eventually the War Department transferred all engineering officers away from Fort Monroe, except Lee, who was ordered to take up residence on the artificial island of Rip Raps across the river from Fort Monroe, where Fort Wool would eventually rise, and continue work to improve the island. Lee duly moved there, then discharged all workers and informed the War Department he could not maintain laborers without the facilities of the fort.[40]

In 1834, Lee was transferred to Washington as General Gratiot's assistant.[41] Lee had hoped to rent a house in Washington for his family, but was not able to find one; the family lived at Arlington, though Lieutenant Lee rented a room at a Washington boarding house for when the roads were impassable.[42][citation not found] In mid-1835, Lee was assigned to assist Andrew Talcott in surveying the southern border of Michigan.[43] While on that expedition, he responded to a letter from an ill Mary Lee, which had requested he come to Arlington, "But why do you urge my immediate return, & tempt one in the strongest manner[?] ... I rather require to be strengthened & encouraged to the full performance of what I am called on to execute."[32] Lee completed the assignment and returned to his post in Washington, finding his wife ill at Ravensworth. Mary Lee, who had recently given birth to their second child, remained bedridden for several months. In October 1836, Lee was promoted to first lieutenant.[44]

Lee served as an assistant in the chief engineer's office in Washington, D.C. from 1834 to 1837, but spent the summer of 1835 helping to lay out the state line between Ohio and Michigan. As a first lieutenant of engineers in 1837, he supervised the engineering work for St. Louis harbor and for the upper Mississippi and Missouri rivers. Among his projects was the mapping of the Des Moines Rapids on the Mississippi above Keokuk, Iowa, where the Mississippi's mean depth of 2.4 feet (0.7 m) was the upper limit of steamboat traffic on the river. His work there earned him a promotion to captain. Around 1842, Captain Robert E. Lee arrived as Fort Hamilton's post engineer.[45]

Marriage and family

Robert E. Lee, around age 38, and his son William Henry Fitzhugh Lee, around age 8, c.1845While Lee was stationed at Fort Monroe, he married Mary Anna Randolph Custis (1808–1873), great-granddaughter of Martha Washington by her first husband Daniel Parke Custis, and step-great-granddaughter of George Washington, the first president of the United States. Mary was the only surviving child of George Washington Parke Custis, George Washington's stepgrandson, and Mary Lee Fitzhugh Custis, daughter of William Fitzhugh[46] and Ann Bolling Randolph. Robert and Mary married on June 30, 1831, at Arlington House, her parents' house just across from Washington, D.C. The 3rd U.S. Artillery served as honor guard at the marriage. They eventually had seven children, three boys and four girls:[citation needed]

George Washington Custis Lee (Custis, "Boo"); 1832–1913; served as major general in the Confederate Army and aide-de-camp to President Jefferson Davis, captured during the Battle of Sailor's Creek; unmarriedMary Custis Lee (Mary, "Daughter"); 1835–1918; unmarriedWilliam Henry Fitzhugh Lee ("Rooney"); 1837–1891; served as major general in the Confederate Army (cavalry); married twice; surviving children by second marriageAnne Carter Lee (Annie); June 18, 1839 – October 20, 1862; died of typhoid fever, unmarriedEleanor Agnes Lee (Agnes); 1841 – October 15, 1873; died of tuberculosis, unmarriedRobert Edward Lee, Jr. (Rob); 1843–1914; served as captain in the Confederate Army (Rockbridge Artillery); married twice; surviving children by second marriageMildred Childe Lee (Milly, "Precious Life"); 1846–1905; unmarriedAll the children survived him except for Annie, who died in 1862. They are all buried with their parents in the crypt of the Lee Chapel at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia.[citation needed]

Lee was a great-great-great grandson of William Randolph and a great-great grandson of Richard Bland.[47] He was also related to Helen Keller through Helen's mother, Kate, and was a distant relative of Admiral Willis Augustus Lee.[citation needed]

On May 1, 1864, General Lee was at the baptism of General A.P. Hill's daughter, Lucy Lee Hill, to serve as her godfather. This is referenced in the painting Tender is the Heart by Mort Künstler.[48] He is the godfather of actress and writer Odette Tyler, the daughter of brigadier general William Whedbee Kirkland.[49]

Mexican–American War

Robert E. Lee around age 43, when he was a brevet lieutenant-colonel of engineers, c. 1850Lee distinguished himself in the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). He was one of Winfield Scott's chief aides in the march from Veracruz to Mexico City. He was instrumental in several American victories through his personal reconnaissance as a staff officer; he found routes of attack that the Mexicans had not defended because they thought the terrain was impassable.

He was promoted to brevet major after the Battle of Cerro Gordo on April 18, 1847.[50] He also fought at Contreras, Churubusco, and Chapultepec and was wounded at the last. By the end of the war, he had received additional brevet promotions to lieutenant colonel and colonel, but his permanent rank was still captain of engineers, and he would remain a captain until his transfer to the cavalry in 1855.

For the first time, Robert E. Lee and Ulysses S. Grant met and worked with each other during the Mexican–American War. Close observations of their commanders constituted a learning process for both Lee and Grant.[51] The Mexican–American War concluded on February 2, 1848.

After the Mexican War, Lee spent three years at Fort Carroll in Baltimore harbor. During this time, his service was interrupted by other duties, among them surveying and updating maps in Florida. Cuban revolutionary Narciso López intended to forcibly liberate Cuba from Spanish rule. In 1849, searching for a leader for his filibuster expedition, he approached Jefferson Davis, then a United States senator. Davis declined and suggested Lee, who also declined. Both decided it was inconsistent with their duties.[52][53]

Early 1850s: West Point and TexasThe 1850s were a difficult time for Lee, with his long absences from home, the increasing disability of his wife, troubles in taking over the management of a large slave plantation, and his often morbid concern with his personal failures.[54]

In 1852, Lee was appointed Superintendent of the Military Academy at West Point.[55] He was reluctant to enter what he called a "snake pit", but the War Department insisted and he obeyed. His wife occasionally came to visit. During his three years at West Point, Brevet Colonel Robert E. Lee improved the buildings and courses and spent much time with the cadets. Lee's oldest son, George Washington Custis Lee, attended West Point during his tenure. Custis Lee graduated in 1854, first in his class.[56]

Lee was enormously relieved to receive a long-awaited promotion as second-in-command of the 2nd Cavalry Regiment in Texas in 1855. It meant leaving the Engineering Corps and its sequence of staff jobs for the combat command he truly wanted. He served under Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston at Camp Cooper, Texas; their mission was to protect settlers from attacks by the Apache and the Comanche.

Late 1850s: Arlington plantation and the Custis slaves

Arlington House, ArlingtonMary Custis's inheritance in 1857

Christ Church, Alexandria, where the Lees worshipedIn 1857, his father-in-law George Washington Parke Custis died, creating a serious crisis when Lee took on the burden of executing the will. Custis's will encompassed vast landholdings and hundreds of slaves balanced against massive debts, and required Custis's former slaves "to be emancipated by my executors in such manner as to my executors may seem most expedient and proper, the said emancipation to be accomplished in not exceeding five years from the time of my decease."[57] The estate was in disarray, and the plantations had been poorly managed and were losing money.[58] Lee tried to hire an overseer to handle the plantation in his absence, writing to his cousin, "I wish to get an energetic honest farmer, who while he will be considerate & kind to the negroes, will be firm & make them do their duty."[59] But Lee failed to find a man for the job, and had to take a two-year leave of absence from the army in order to run the plantation himself.

Lee's cruelty on the Arlington plantation nearly led to a slave revolt, since many of the slaves had been given to understand that they were to be made free as soon as Custis died, and protested angrily at the delay.[60] In May 1858, Lee wrote to his son Rooney, "I have had some trouble with some of the people. Reuben, Parks & Edward, in the beginning of the previous week, rebelled against my authority—refused to obey my orders, & said they were as free as I was, etc., etc.—I succeeded in capturing them & lodging them in jail. They resisted till overpowered & called upon the other people to rescue them."[59] Less than two months after they were sent to the Alexandria jail, Lee decided to remove these three men and three female house slaves from Arlington, and sent them under lock and key to the slave-trader William Overton Winston in Richmond, who was instructed to keep them in jail until he could find "good & responsible" slaveholders to work them until the end of the five-year period.[59]

Lee ruptured the Washington and Custis tradition of respecting slave families and by 1860 he had broken up every family but one on the estate, some of whom had been together since Mount Vernon days.[61]

The Norris caseIn 1859, three of the Arlington slaves—Wesley Norris, his sister Mary, and a cousin of theirs—fled for the North, but were captured a few miles from the Pennsylvania border and forced to return to Arlington. On June 24, 1859, the anti-slavery newspaper New York Daily Tribune published two anonymous letters (dated June 19, 1859[62] and June 21, 1859[63]), each claiming to have heard that Lee had the Norrises whipped, and each going so far as to claim that the overseer refused to whip the woman but that Lee took the whip and flogged her personally. Lee privately wrote to his son Custis that "The N. Y. Tribune has attacked me for my treatment of your grandfather's slaves, but I shall not reply. He has left me an unpleasant legacy."[64]

Wesley Norris himself spoke out about the incident after the war, in an 1866 interview printed in an abolitionist newspaper, the National Anti-Slavery Standard. Norris stated that after they had been captured, and forced to return to Arlington, Lee told them that "he would teach us a lesson we would not soon forget." According to Norris, Lee then had the three of them firmly tied to posts by the overseer, and ordered them whipped with fifty lashes for the men and twenty for Mary Norris. Norris claimed that Lee encouraged the whipping, and that when the overseer refused to do it, called in the county constable to do it instead. Unlike the anonymous letter writers, he does not state that Lee himself whipped any of the slaves. According to Norris, Lee "frequently enjoined [Constable] Williams to 'lay it on well, ' an injunction which he did not fail to heed; not satisfied with simply lacerating our naked flesh, Gen. Lee then ordered the overseer to thoroughly wash our backs with brine, which was done."[60][65]